Jerome Kern. Photo courtesy landing.com

On this edition of Riverwalk Jazz, it’s a collection of love songs from a remarkable era of American songwriting in the first half of the twentieth century that produced the timeless music of Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen, Cole Porter, Harry Warren, the Gershwin brothers and many more tunesmiths who remain “unsung.” The great body of work produced during this “Golden Age of American Songwriting” is often collectively referred to as “The Great American Songbook.”

Jerome Kern and lyricist Otto Harbach created “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” for their 1933 Broadway stage production Roberta. Kern’s original conception of the tune was as a staccato accompaniment for a tap dance number, in front of the curtain during a scene change, but he was persuaded to slow the tempo down to let the melody soar. Clifford Brown, Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, Sonny Rollins, Thelonius Monk, Charlie Parker, Art Tatum and Sarah Vaughan have recorded significant jazz versions. Our version this week features the two clarinets of Evan Christopher and Brian Ogilvie.

.jpg)

Carol Woods with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. Photo courtesy Rivewalk Jazz.

“Meet Me Tonight In Dreamland” was one of the most famous and beloved popular songs of the early twentieth century. Written as a waltz in 1909, the tune is one of many early twentieth century “parlor songs” adapted by the two titans of jazz reeds Bob Wilber and Kenny Davern for their celebrated collaboration of the 1970s known as Soprano Summit. For our show, Bob Wilber teams up with Cullum Band clarinetist Allan Vaché to recall the exceptionally hot, swinging energy of that group.

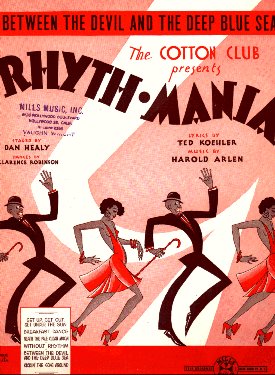

Rhythmania. Image courtesy songbook1.

The blues-inflected genius of Harold Arlen is well represented this week with three songs: “Between The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea” from Rhythmania, the first revue produced at Harlem’s Cotton Club in 1927. Arlen and other songwriters composed many of their biggest hits for subsequent Cotton Club revues, often for the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Cotton Club revues influenced the development of Broadway shows and became nationally famous through network radio broadcasts from its stage.

“Come Rain or Come Shine” comes from a later period in Arlen’s career and his frequent collaboration with Johnny Mercer. Later, this number would become an often-recorded jazz standard, but it was created for the 1946 Broadway stage musical, St. Louis Woman. The original cast included the Nicholas Brothers and Pearl Bailey. “A Sleepin' Bee” was introduced by Diahann Carroll in the 1954 stage musical House of Flowers. Arlen’s lyricist this time was the celebrated author Truman Capote. Later, both Mel Tormé and Nancy Wilson recorded landmark jazz versions. The unique arrangement for The Jim Cullum Jazz Band heard here was penned by pianist John Sheridan and features trombonist Mike Pittsley.

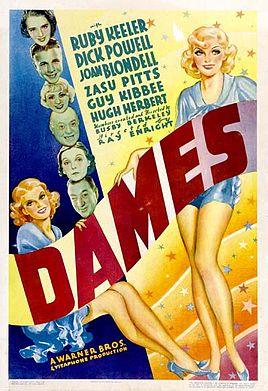

Dames. Image courtesy Wikimedia.

Harry Warren never became as famous as Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, or the Gershwins, perhaps because Warren was the first major American songwriter to write primarily for film, where songwriters typically took a backseat to movie stars and directors. Harry Warrens songwriting output was on a par with the other major players of the era, especially in the number of high quality hits that later became jazz standards. His “I Only Have Eyes for You,” from the 1934 Busby Berkeley movie musical Dames, is included in the list of the 25 most performed songs of the twentieth century as compiled by the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP).

Billie Holiday, 1947. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Billie Holiday remains a unique and highly influential icon of jazz singing. Throughout her career from the 1930s to the 50s, Holiday was acutely aware of her own musical identity. She said, “I hate straight singing. I have to change a tune to my own way of doing it. That’s all I know,” and “If I’m going to sing like someone else, then I don’t need to sing at all.” Our show this week features three of her most famous recorded tunes, “Lover Man, Oh Where Can You Be?” “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” and “Body and Soul,” all interpreted by stage, film and TV personality—Carol Woods.

.jpg)

Jim Cullum and Eddie Torres with Benny Carter. Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Multi-instrumentalist and composer Benny Carter set a high standard of excellence in a distinguished career in jazz that spanned some seven decades. Fortune smiled on the Riverwalk Jazz radio series when Carter appeared as a guest in 1992. John Sheridan’s arrangement of Carter’s “When Lights are Low” features Carter’s original “bridge”—an especially challenging section noted for its travel through four tonal centers in eight bars. This daunting musical challenge was famously avoided by Miles Davis in his simplified version in 1956, for the album Cookin.’ This version of the tune with what some jazzmen consider its “dumbed-down” bridge has gained currency in the modern jazz world.

Cullum Band arranger John Sheridan says, “When I began writing the arrangements for this show with Benny Carter, I called him at his home in California, and we discussed “When Lights are Low” and the other tunes on the show. When Benny came to the Landing and he heard my arrangements of his tunes, I was very happy to know that he was pleased with them.”

Most people are familiar with Gene Kelly’s song and dance version of “Singin' in the Rain” in the 1952 eponymous Hollywood movie musical. Our guest, the great Count Basie Band veteran singer Joe Williams, put his own jazz stamp on the tune, performing and recording it soon after the movie’s release and often thereafter, and he shares it with us on this show.

.jpg)

Joe Williams at The Landing. Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Irving Berlin created “How Deep Is the Ocean?” in 1932. Unusually, it became a hit not by its inclusion in a Broadway show or Hollywood movie musical, but through the relatively new medium of radio. Berlin shares with Cole Porter the distinction of being the only major songwriters of the Golden Age who did not collaborate with lyricists. Porter and Berlin always wrote their own lyrics to their melodies. “How Deep” became a jazz standard through recordings by Benny Goodman (with Peggy Lee), Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat Cole and in the modern jazz world through a 1961 recording by the harmonically adventurous pianist Bill Evans. Our version this week features Australian songstress Nina Ferro.

Vernel Bagneris. Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Playwright/actor/producer Vernel Bagneris is a lifelong student of the history of Black Musical Theater. Vernel is featured this week on two songs from the team of Thomas “Fats” Waller and lyricist Any Razaf. “Ain’t Misbehavin,’” first introduced in the 1929 revue Hot Chocolates, also features piano master Dick Hyman in tribute to the composer’s legendary pianistic prowess in the “Harlem stride” style. Another Waller/Razaf collaboration with a vocal by Vernel Bagneris dates from 1938, “I Had To Do It.”

Photo credit on Home Page: Jerome Kern courtesy landing.com

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1997