Newly restored Empire stage. Photo courtesy of Empire Theatre.

This edition of Riverwalk Jazz celebrates the grand opening of the Charline McCombs Empire Theater in San Antonio in 1998 after a $5 million renovation spearheaded by the Las Casas Foundation. Originally designed in the style of a European palazzo in 1913, The Empire served as a vaudeville house and then a movie theater. The disastrous flood of downtown San Antonio in 1921 caused extensive damage to the theater and hasty repairs dimmed the luster of the original décor. In 1978 the Empire closed its doors and gathered cobwebs, but now the Empire’s newly restored plasterwork glitters under a dazzling frosting of gold leaf. The 900-seat Empire is a jewel box theater listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Tonight, music students from high schools across the city pack the balcony for this inaugural performance. Hundreds of community figures are on hand, including entrepreneur and civic leader Red McCombs who helped make this beautiful restoration a reality for the people of San Antonio.

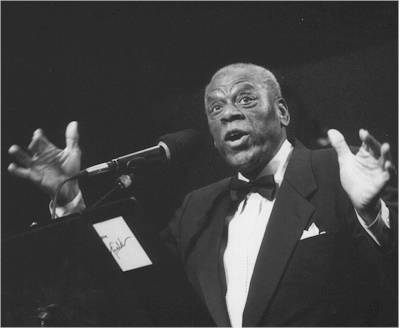

William Warfield. Photo courtesy of Riverwalk Jazz.

The opening night broadcast is titled, Clarinets and Cornets: The Streets of New Orleans, and stars The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. In the role of narrator is theater and film legend, William Warfield, who brings to life first person accounts of musicians who witnessed the early days of New Orleans jazz.

The Cullum band opens the celebration with the familiar New Orleans brass band march “High Society,” composed in 1901 by Porter Steele. King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band recorded the most famous jazz recording of this number for the Gennett label in 1923.

It’s said that early 20th century cornet legend Buddy Bolden was ‘the first’ in a long line of New Orleans jazzmen to earn the title “King” from fellow musicians and band followers. “Buddy Bolden’s Blues,” made famous by Jelly Roll Morton and recorded widely in the modern era, was originally known as “Funky Butt.” Bolden and his band created this piece in the very early days before the music had acquired the name ‘jazz.’ At the time, and for some today, the lyrics of this bluesy number would be considered rude and not at all appropriate for polite company. Trombonist Kid Ory recalled Bolden attending church, “not for religion,” but to get musical ideas for his tunes. His classic “Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor” has the flavor of a Gospel Hymn.

Buddy Bolden Band. Photo courtesy of Frank Driggs.

Jelly Roll Morton’s recollection of Buddy Bolden is tinged with Jelly’s usual enthusiasm and bold exaggeration:

“Speaking of swell people I might mention Buddy Bolden, the most powerful trumpet player I’ve ever heard. I remember we’d be hangin’ around some corner. We wouldn’t know there was going to be a dance out at Lincoln Park, then we’d hear old Buddy’s trumpet comin’ on, and the whole town would know that Bolden was at the park—ten or twelve miles from the center of town. He was the blowing-est man since Gabriel.”

Jelly Roll Morton. Photo in public domain.

Jelly’s famous claim to be the “inventor of jazz, blues and stomps” may be an exaggeration, but he was the first jazz musician to notate and publish his compositions, thus codifying the musical language of the genre. Another of Jelly’s classic tunes featured by Jim Cullum and his Band on this broadcast is “The Pearls.”

Dating from the World War I era, “Song of Songs” became a signature tune for New Orleans reedman Sidney Bechet, widely considered one of the first great soloists in jazz. Jim Cullum Jazz Band clarinetist Evan Christopher, a life-long student of early New Orleans clarinet masters, gives us his interpretation of “Song of Songs,” very much in the expansive Bechet style.

Evan Christopher. Photo courtesy of the artist.

On this broadcast, Evan offers a musical demonstration of the difference in sound between two different types of clarinets used in jazz: the conventional modern instrument that uses the Boehm fingering scheme and the more primitive, conically-shaped “Albert system” instrument favored by the older New Orleans players. Evan says, “I prefer the Albert for the rough stuff, the low-down, ratty, sexy blues. The soul of New Orleans is in this horn with its rich, broad tone, especially in the lower register.” On this radio show, we hear Sidney Bechet’s original 1940s recording of “Blue Horizon” then a live cross-fade to the stage of The Empire Theater with Evan Christopher playing his “Albert system” clarinet with the Band. Rounding out our trio of Bechet classics is “Sweetie Dear,” an especially hot band number adapted for The Jim Cullum Jazz Band by arranger and pianist John Sheridan.

King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band. Photo courtesy of Frank Driggs.

King Oliver’s singular protégé Louis Armstrong remains the most highly regarded and widely known of all New Orleans musicians. At the time of his death in 1971, it was said that Armstrong was better known than any other American in the world. Here’s how Louis Armstrong recalled his early days in New Orleans:

“There was so much music when I was growing up in New Orleans that you couldn’t help but hear it. In the evenings people would give parties on the lawns in front of their houses. They had beer, lemonade, sandwiches, fried chicken and gumbo. The band would sit out front in the porch and all the people would dance and have a good time. Buddy Bolden had the biggest reputation, but he just played loud. My favorite was Joe Oliver. Joe was so good to me when I was a kid. When he was marching with the Onward Brass Band he would stop for a rest, and he would let me hold his horn. He knew this meant a lot to me, so he showed me how to put my mouth to his horn and get a note. Joe Oliver was always kind to me. I owe Joe everything. If it hadn’t been for Joe Oliver you wouldn’t have ever heard of me, Louis Armstrong.”

"Weather Bird Rag" record label courtesy of Starr-Gennett Foundation.

To round out this tribute to early New Orleans jazz, Jim Cullum and his band play King Oliver’s “Doctor Jazz” in the style of his Creole Jazz Band of the 1920s. We also hear “Weather Bird Rag,” first recorded in 1923 by Oliver and again in 1928 as a duet with Armstrong and pianist Earl Hines. The Jim Cullum Jazz Band’s special arrangement uniquely combines elements of both versions of “Weatherbird.”

Photo credit for homepage image: Evan Christopher. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1998