1920s' New York was full of young jazz musicians who’d rolled in from somewhere else. Ernest Loring Nichols, a redheaded kid from Utah fell into partnership with a studious-looking trombone player from nearby Long Island named Miff Mole. Instantly they clicked, and together set the standard for hot recording bands of the early 20s. They recorded under an ever-changing roster of goofy names like The Arkansas Travelers, or The Tennessee Tooters—names that seem at odds with the polished skill and urban sound of their hits.

By 1925 Red Nichols was the man to see if you were a musician in New York and needed a job. He was the 'go to' guy, equally connected to record labels needing talent and top-flight musicians looking for work. A well-schooled musician tutored by his bandmaster father, Red could pick up a violin, sit down at the piano or play the cornet. His cornet style has been praised for its “ringing tone and springy, punchy, rhythmic drive.”

When George and Ira Gershwin mounted their 1930 Broadway musical Strike Up the Band, they turned to Red Nichols to put their orchestra together. Nichols filled the chairs in the pit band with rising stars in the jazz world. On opening night as the curtain parted, first-nighters were treated to the sound of Jack Teagarden, Benny Goodman, Jimmy Dorsey and Glenn Miller—all under the baton of Red Nichols.

Red Nichols was a skilled talent scout. His studio sessions were a magnet and proving ground for top, young, white jazz players. Many would go on to become star bandleaders of the Swing Era. In the late summer of 1927 Jack Teagarden had finished a gig in a society dance band at San Antonio’s Gunther Hotel. Impulsively the 25-year-old trombonist hit the road for New York in a Cadillac belonging to the wife of one his band mates. One warm August evening they landed in Times Square. Dropped off at a phone booth in mid-town with his bags and instrument case, the first person Jack called was Red Nichols. Always on the lookout for something new to offer the record-buying public, Red was quick to capture Jack Teagarden’s soulful, blues-driven sound and playful vocals on disc.

Pint-sized with flame-red hair, Red Nichols was a go-getter with a good head for business. And he was clean and precise in his playing, a modernist always exploring new territory. But Nichols’ popular success drew criticism from some who called him an 'entertainer' rather than an 'artist.' Critics saw his success as “selling out” or somehow inauthentic, not true to the spirit of hot jazz as it was played by Jazz Age cornet hero, Bix Beiderbecke.

Richard Sudhalter devotes an entire chapter to “Red Nichols and His Circle” in his monumental 1999 work, Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915—1945. Sudhalter writes:

"With its jauntiness and sense of slightly ironic detachment, their music was “cool,” fully three decades before that term became popular. No other bands, white or black, preceded them in exploring this new psychological territory.

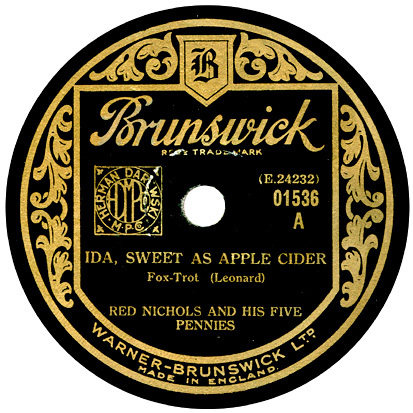

"Ida, Sweet As Apple Cider" Red Nichols recording, 1927. Courtesy 78records.wordpress.

Their records are a delight; varied in tone, color, and texture, full of unusual combinations of instruments, unafraid to import harmonic and structural devices from European music, each performance offers some surprise, some unexpected felicity."

Saxophonist Bud Freeman and his friends often worked in studio groups led by Red Nichols but would not agree with Sudhalter about Nichols' musicianship. Freeman once said, “In the opinion of our group, Nichols was a synthetic player. He was a clever musician and made a lot of records, but he was a very mechanical player.”

This week on Riverwalk Jazz The Jim Cullum Jazz Band tells the story of Red Nichols and his Five Pennies, illustrated with numerous historical recordings of Nichols and the ensembles he led.

In spite of the controversy surrounding his work, Red Nichols was the most recorded and successful musician-bandleader in New York in the 1920s. He led enormously popular bands featuring some of the most creative white jazz players of that time, under names such as The Five Pennies, The Red Heads, and Miff Mole and His Little Molers. This voluminous output of recorded work—Red appeared on about 4,000 recordings in the 1920s—is recognized today as a major expansion and refinement of the harmonic and compositional possibilities in jazz.

Photo credit for Home Page: Red Nichols & Miff Mole, 1925-1927 recordings. Image courtesy amazon.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2012