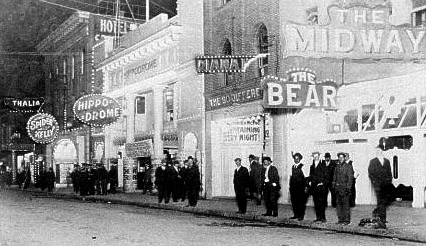

A century ago San Francisco’s Barbary Coast was a waterfront hub of loose living, dance-crazy club-goers and wild new music. The Barbary Coast had been notorious for fifty years before the 1906 earthquake, and within hours of the last trembler its saloons and whorehouses were open for business again.

In a town settled by gold-seekers and rogues, where men far outnumbered women, it was 'sin city' with a rugged western energy. The Barbary Coast was a sideshow, skid row and music mecca all rolled into one. It was here that bandleader and pianist Sid LeProtti made his mark, and traveling jazzmen like King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton came calling.

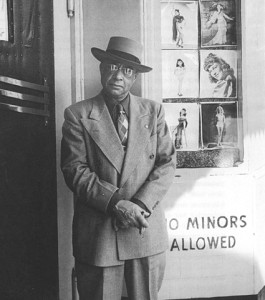

Pianist Sid LeProtti was active on the Barbary Coast in its heyday between 1907 and 1917, leading his band at Lew Purcell’s So Different Cafe. The illegitimate son of an Italian merchant and black woman, Sid inherited his last name from his father, and musical talent from both sides of the family.

In the 1950s Sid Le Protti sat down with San Francisco trombonist and bandleader Turk Murphy to record his memories of the Barbary Coast.

This week on Riverwalk Jazz we hear rare recordings of Sid LeProtti playing piano and actor Vernel Bagneris bringing LeProtti’s words to life. The Jim Cullum Jazz Band plays classic tunes that might have been danced to in the night spots of Pacific Street.

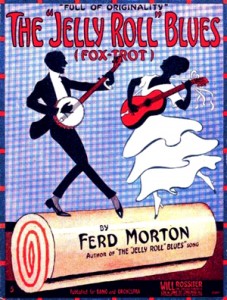

"He’s tall and chancy, a lady’s fancy"—or at least that’s the way Jelly Roll Morton described himself in his song, "Jelly Roll Blues."

The Barbary Coast was a 'way station' for traveling musicians, and Jelly Roll made it there too. Musicians knew they could always pick up work in a band, or cash, playing pool or in a card game. Jelly Roll Morton wasn’t the only New Orleans jazz legend to visit the Barbary Coast. On tour with his Creole Jazz Band in San Francisco, King Oliver sat in with Le Protti’s group more than once.

More than any other influence, the first New Orleans jazz band to visit the West Coast had a profound effect on Sid LeProtti’s concept of what a jazz band should be. The propulsive beat of Will Johnson’s Original Creole Orchestra gave the music a new kind of excitement and LeProtti wanted that rhythm for his band too. He found himself a new drummer and added a string bass to his band at Purcell's because that was "the Louisiana-type thing to do."

A crusade started up by the Reverend Paul Smith in 1916 was the beginning of the end of the Barbary Coast. When a San Francisco newspaper got on the ‘band wagon,' the police commissioner decided they had to clean up the district. It took five years to do the job. They cracked down on prostitution first, and put all the sporting houses out of business. They got tough with dance halls, prohibiting dancing anywhere in the Barbary Coast. Finally they put a stop to the music.

Sid LeProtti played his last note on Pacific Street one night in the spring of 1921.

Turk Murphy. Photo courtesy SF Traditional Jazz Foundation.

This broadcast is dedicated to the legacy of trombonist Turk Murphy and author Tom Stoddard, whose passion for the history of the Barbary Coast helped create the source materials on which this program is based, in part. Thanks also to Bill Carter of the San Francisco Traditional Jazz Foundation.

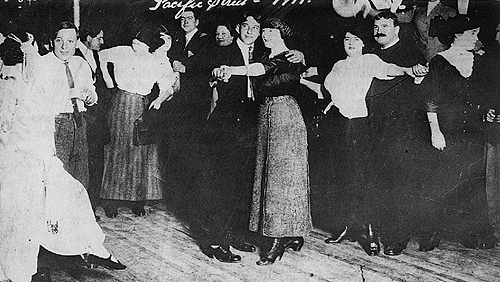

Photo credit for Home Page: Dancers at Spider Kelly’s, 1913. Photo courtesy Jazz on the Barbary Coast by Tom Stoddard

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick© 2010