On this live radio show, Riverwalk Jazz recalls the big, brassy sound of King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band in a concert recorded at Dinkelspiel Auditorium at the renowned Stanford Jazz Workshop on the campus of Stanford University. Joining The Jim Cullum Jazz Band this week, theater legend William Warfield reads excerpts from King Oliver’s personal letters, and veteran traditional jazz players cornetist Leon Oakley and tubist Mike Walbridge sit in with the band.

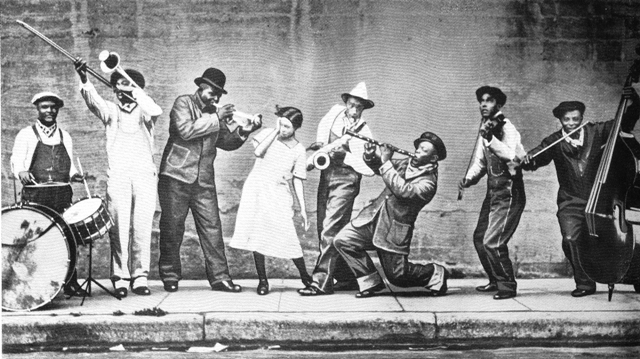

King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, 1921. Left to right: Ram Hall, Honore Dutrey, King Oliver, Lil Hardin, David Jones, Johnny Dodds, Jimmie Palao, Ed Garland. Courtesy of The Frank Driggs Collection.

The concert opens with a tune often played by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band— “Frog-I-More Rag” composed by Jelly Roll Morton. Published in 1918, it’s thought that Morton titled the tune after a vaudeville performer known as Frog-Eye Moore. Morton later separated out the last section of the composition and played it at a much slower tempo, resulting in the ballad “Sweetheart O’ Mine.”

.jpeg)

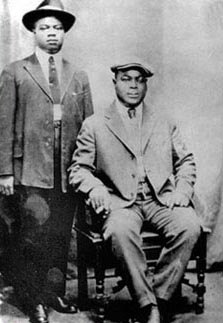

Joe 'King' Oliver. Photo courtesy of The Duncan Scheidt Collection.

Coming of age in New Orleans, Joe Oliver cut his teeth on the sound of the Eagle and the Onward brass bands. In neighborhoods across the Crescent City, he would hear bands playing outdoors for any and all occasions, from baptisms and picnics to ‘fish frys’ and funerals. Joe Oliver’s fascination with the cornet was the driving force in his life. Blowing down his rivals in cutting contests on the streets of New Orleans earned him the title “King.”

It was natural for Louis Armstrong to gravitate towards Joe ‘King’ Oliver, as a boy, following in the older man’s footsteps along the parade route and carrying the King’s horn between tunes. A close bond developed between the two, and it wasn’t long before King Oliver became “Papa Joe” to young Louis.

"Dippermouth Blues" record label, 1923. Image courtesy of The Starr-Gennett Foundation.

In the early 1920s King Oliver and Louis Armstrong made jazz history playing together night after night to packed houses on the South Side of Chicago in dance halls like the Lincoln Gardens. On this radio show, we play a fragment of Oliver’s 1923 recording of “Dippermouth Blues,” followed by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band going full tilt with cornetist Leon Oakley and tuba player Mike Walbridge. Composed by Oliver, “Dippermouth” got its title from one of the many nicknames attached to Louis Armstrong.

Joe Oliver’s letters have survived as a priceless record of his personal reflections on his journey as a musician, and offer insights into his character. Our special guest, the renowned stage and film actor William Warfield brings King Oliver’s thoughts to life. The first piece William Warfield reads is a letter Oliver wrote to his friend, the New Orleans cornetist Bunk Johnson:

William Warfield. Photo courtesy of University of Rochester.

“Dear Bunk: I received your letter and was glad to hear from you and know you are enjoying God’s best blessing, which is good health. This leaves me well. Well, pal, I’ve got you some. I’m a grandfather now. But I’m sure you will be kind enough to admit that I’m a few years younger than you are. I know you remember when I used to come around and listen to you play. Now Bunk, it’s your fault you are down there working for nothing. I had two good jobs for you. I did all I could to locate you but failed. If I know how and where to reach you it will mean a wonderful break for you. In the meantime, I will send you a few numbers to arrange. I can give you some extra change as a sideline. Have you got any good blues? If so, send them to me, and I will make them bring you some real money. When making my arrangements, always write the cornet a real low-down solo ‘a la Bunk. Remember how you used to drive the blues down? Remember Second and Magazine Streets, when Walter Brundy would talk to me while you’d steal my music? I often think about those days. Looking to hear from you real soon. I remain with kind regards, very truly yours, Joseph Oliver.”

Broadcast Playlist Notes

A young Louis Armstrong standing beside "Papa Joe." Photo courtesy of neajazzintheschools.org.

The King Oliver Creole Jazz Band recorded “Riverside Blues,” composed by Richard M. Jones and Thomas A. Dorsey, in 1923 for the Okeh label in Chicago. With the addition of Louis Armstrong on second cornet, Oliver and his band were at the peak of their power and cohesiveness. “I Ain't Gonna Tell Nobody” also dates from this period.

“Too Late” is one of a series of discs made in 1929 in New York under Oliver’s name for the Victor label. These sessions turned out to be his last recordings as a bandleader. By then, Joe Oliver had serious gum disease and, unable to play on many of these tracks, he had to hire other trumpeters to take his parts. The Cullum Band arrangement and performance of this tune bring to it a degree of energy and virtuosity never imagined by its creators.

When Louis Armstrong left King Oliver’s band his career quickly took off on its own trajectory. “Some of These Days” was a mega-hit for vaudevillian Sophie Tucker in 1926, and Armstrong’s 1929 recording brought a new jazz feeling to the tune that remains in effect to this day. “Lying To Myself” by Hoagy Carmichael proved to be a great vehicle for Armstrong, whose star was continuing to rise in 1936 just as the sun was setting on King Oliver’s virtuosity.

By November 1937 Joe Oliver was not playing music at all anymore. He had a job sweeping the floors in a pool hall in Savannah, Georgia. Nobody knew the ‘great man’ pushing the broom. William Warfield reads a letter Oliver wrote to his old friend from New Orleans, the bassist Pops Foster:

Pops Foster. Photo courtesy SF Trad Jazz Foundation.

“Pops—breaks come to cats in this racket only once in a while, and I guess I must have been asleep when mine came. I made lots of dough in this game but I didn’t know how to take care of it. I’d helped to make some of the best names in the music game, but I’m too much of a man to ask those who I’ve helped to help me. Some of the guys I have helped are responsible for my downfall in a way. I’m a guy who took a pop bottle and a rubber plunger and made the first mute ever used in a horn. But I didn’t know how to get a patent for it, and some educated cat came along and made a fortune off my ideas. I’ve written a lot of numbers that someone else got the credit and the money for. I couldn’t help it because I didn’t know what to do. I’ve been under the management of both colored and white bookers for the last few years, and I haven’t had one yet to deal fair with me. I’m in terrible shape now. I’m getting old and my health is failing. Very Truly Yours, Joseph Oliver.”

To close the concert, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band plays “West End Blues,” composed by King Oliver and recorded by the Louis Armstrong Hot 5 with Earl Hines in 1928. This record is often singled out by jazz critics, writers and documentary filmmakers as the finest work of early jazz ever captured on disc. Armstrong’s recorded performance continues to inspire jazz musicians, including Jim Cullum, to this day.

Photo credit for Home Page: King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, 1923. Photo courtesy redhotjazz.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1996