If you stepped into New Orleans' Lyric Theater, the '81' on Decatur Street in Atlanta—or a dusty tent show down any country road, you’d discover a gem of popular culture. In the early 1900s Black Vaudeville boasted stars like the ragtime duo Sissle and Blake, blues "belter" Ma Rainey or comedy sketches by the bickering lovebirds Butterbeans and Susie.

Listening to his grandmother tell stories about going to see shows at New Orleans’ Lyric Theater inspired Vernel Bagneris to find out all he could about music and comedy in Black Vaudeville, and led him to create his hit revue, One Mo' Time.

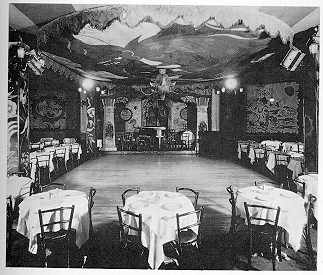

One of the most popular venues on the T.O.B.A. (Theater Owner's Booking Association) circuit, The Lyric Theater presented acrobats and opera singers, black-faced comedians, blues, jazz and eccentric dancers. People would watch what they liked, then go out in the alley to smoke and talk with friends, until the next act they liked came on.

Vernel compares his discovery of Black Vaudeville to “drinking pasteurized milk all your life and then getting it ‘fresh from a cow’ for the first time." He says the attitude of Black Vaudeville was "in the pocket" with the way he felt in the 1970s. You could put a whole lot into a song that you couldn’t say outright. Messages of hope—or anger—were sometimes just under a happy-go-lucky surface.

In the late 1970s, Vernel’s One Mo' Time, which would become a huge Off-Broadway hit, debuted in New Orleans at the same theater he’d heard so much about from his grandmother. Even the story of his show was set in The Lyric Theater.

One of the great vaudeville stars who came to see Vernel’s re-creation was ragtime pianist and composer Eubie Blake. A half-century earlier, Blake’s landmark 1921 musical Shuffle Along was a box office hit. The first all-black musical to get Broadway billing—it broke racial barriers for New York theater-goers. For the first time, blacks were allowed to purchase orchestra seats next to white patrons. The best-remembered hit song from Shuffle Along is still "I'm Just Wild About Harry."

Butterbeans and Susie were household names in Black Vaudeville for five decades. They battled their way through bawdy sketches, with Susie playing a no-nonsense ‘tough cookie’ to Butter’s 'no-good man.' On our broadcast this week, New Orleans' vocalist Topsy Chapman joins Vernel to remember Butterbeans and Susie routines with "Not Until Then" and the ribald "Elevator Poppa, Switchboard Momma."

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey was a star attraction in the biggest traveling shows in the business—Tolliver’s Circus and The Rabbit Foot Minstrels. As early as 1902 she was singing the blues in giant stage shows that traveled the South under the Big Top. A gang of roustabouts set up tents for shows with dozens of dancers, magic acts, jugglers, strong men and more. Topsy pays tribute to Ma Rainey with "Jelly Bean Blues."

Nightclubs on the Southside of Chicago of the 1920s borrowed heavily from vaudeville for their elaborate floorshows. By the end of most evenings even artists like Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines wound up getting into the act. Vernel recalls Armstrong and Hines taking part in a Charleston contest on stage at one of the most famous Southside 'black and tans' and joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band on "Sunset Cafe Stomp."

By the end of the 1920s black musical revues were a staple on Broadway, and many of them had made their debuts in Harlem nightclubs. Connie’s Inn, a basement club on 131st Street, promised patrons a “lowdown treat” with the new Fats Waller-Andy Razaf show, Hot Feet.

It opened to rave reviews, and within the year the producers decided to move it to Broadway. They gave their show a new name, Hot Chocolates, and brought in the bootlegger who supplied liquor to their club to front the cash. Hot Chocolates would give Waller and Razaf their biggest hit—"Ain’t Misbehavin." And it made them the composers of the first racial protest song "What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue?"

Vernel Bagneris recites the lyrics to "Black and Blue" with Dick Hyman at the piano. The Jim Cullum Jazz Band closes the show with a hot blues on the W.C. Handy number, "Chantez les Bas," or "Sing 'em Low."

Photo credit for Home Page: Vernel Bagneris as "Papa Du." Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2008