Adolphe Sax photo courtesy Wikimedia.

The saxophone, like its cousin the clarinet, is classified as a single-reed woodwind instrument. Belgian instrument maker Adolphe Sax invented and patented the first one in Paris in 1846. It developed a reputation for being easy to play and combined the speed of woodwinds with the carrying power of brass, so the saxophone became the hula hoop of its day. Today, the saxophone has an important place in nearly every kind of music from classical and jazz to rock and salsa.

Joining us this week is guest artist Ken Peplowski, one of the top reed players in the world of jazz. He has recorded and performed with Benny Goodman, Mel Tormé, Peggy Lee, Dick Hyman and George Shearing. Jim Cullum says, “Ken brings a new excitement to classic jazz.”

W.C. Handy is credited as the first composer to use a saxophone in an American orchestra as the musical director of a concert wind band in 1909 in Mississippi. He described the sound of the saxophone as “the moaning of a sinner on Revival Day.” The saxophone began to be heard in jazz bands in the Roaring 20s on anthems of the era like “Jazz Me Blues,” a Cullum Band favorite performed here with special guest Ken Peplowski. New Orleans clarinetist Jimmie Noone put together his band at the Apex Club in Chicago using alto sax and clarinet in the front line, rather than the traditional line-up of cornet, clarinet and trombone. A popular number they recorded in 1930 is “San,” heard here with Ken ‘Peps’ Peplowski sitting in on alto with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

W.C. Handy and his Memphis Orchestra, 1918. Handy is in rear center with moustache. Photo in public domain.

Body and Soul” Bluebird label for Coleman Hawkins. Image courtesy boogiewoogieflu

Coleman Hawkins remains a key figure in the development of the saxophone as a jazz instrument. Hawkins was the first saxophonist to rise to stardom as a soloist in the jazz world. A prodigy and multi-instrumentalist, Hawkins learned to play the piano when he was five, the cello at seven and the tenor saxophone at nine. In the 1920s he toured with blues singer Mamie Smith and Fletcher Henderson in the US; and then in the 1930s he achieved international fame recording and performing in Europe with Benny Carter and Django Reinhardt. In 1939 Hawkins had a smash hit on the Bluebird label with his recording of “Body and Soul.” Today Hawkins’ improvisation on this record is considered a cornerstone of saxophone jazz. Our ensemble offers their homage to Coleman Hawkins’ masterpiece.

Saxophone by Adolphe Sax. Photo courtesy orgs.eds.edu.

In the early 1930s when Lester Young first jobbed around as a tenor saxophonist in “territory bands” in the Midwest and throughout the southwestern states, Coleman Hawkins had the jazz world under his spell. Hawkins set the standard for how the tenor sax should be played in jazz, but Lester Young had no intention of imitating Hawkins, or anyone else. One of Lester’s early breaks came when he was hired for Fletcher Henderson’s group in New York as Coleman Hawkins’ replacement. Somehow Lester just didn’t fit into the ensemble. At one point, Fletcher Henderson was so dissatisfied with Lester’s contribution on the bandstand, he forced Young into lengthy coaching sessions with Henderson’s wife. Lester was made to spend hours listening to Coleman Hawkins records, with the idea of making him play more like Hawkins. Lucky for the jazz world, it didn’t work out. Lester continued to develop his own highly individual jazz saxophone style; a prettier, more lyrical sound than Coleman Hawkins. On this radio show, Ken Peplowski demonstrates the difference between the styles of Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young.

Peplowski says, “Coleman Hawkins played much more like a piano player. He tended to really understand the harmonic ideas behind a song and really outline the chord changes…Lester Young played much more rhythmically and with a smoother sound that tended to take things in another direction, skimming over the top of the chord changes. He created a whole style that influenced saxophone players much later, like Stan Getz, Zoot Sims and myself, and even Charlie Parker.” Peplowski goes on to give advice to students of jazz saxophone: “The best thing to do is to listen to as many people as possible and find your own way to play…you take from the past and try to move it one step further.”

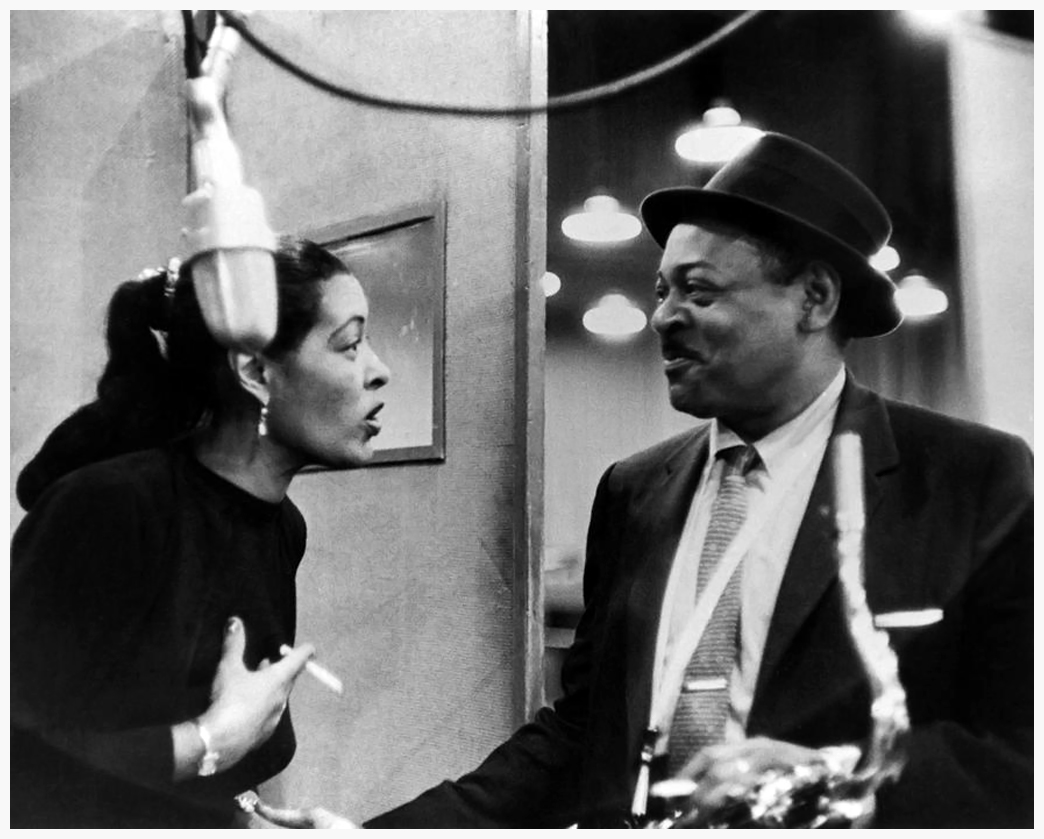

Billie Holiday and Coleman Hawkins. Photo courtesy the Frank Driggs Collection.

Playing together at the Reno Club in Kansas City, Lester Young and Herschel Evans became lifelong friends and competitors. Evans followed the Hawkins school and Lester followed his own star. On our show, Peplowski and Cullum Band reedman Brian Ogilvie pay tribute to the epic Young-Evans “tenor battles” of the Basie Band with “Tickle Toe.” “Blue and Sentimental” is a ballad typical of Young and Evans playing together.

Jim Cullum says, “A lot of this music has its roots in Kansas City, which was a wide-open town in the 1930s. The music scene benefitted from all the loose cash floating around the saloons and high-stakes gambling. Count Basie and his orchestra held forth there for years—famous for their live broadcasts from the Reno Club. Kansas City was a hotbed for boogie woogie, blues and Basie-style swing. They say Kansas City was the birthplace of the jam session. Great musicians were in and out of town all the time, Big Joe Turner, Coleman Hawkins, Jimmy Rushing—they were all a part of this incredible scene.“

Johnny Hodges and Al Sears, NYC 1946 by Wm Gottlieb, courtesy Library of Congress.

Series host David Holt tells the story of a legendary face-off between Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young on the bandstand of Kansas City’s celebrated nightspot, the Cherry Blossom.

Johnny Hodges was a mainstay of the Duke Ellington Orchestra from 1928 through 1951, one of many musicians influenced by Lester Young’s lyrical style. Hodges’ main instrument was the Eb alto saxophone although he also played the Bb soprano. Early on he was a protégé of New Orleans reedman Sidney Bechet. Hodges had difficulty reading music arrangements but was a brilliant improviser, renowned for his fabulous solos with the Ellington Orchestra. “Toasted Pickle” is an Ellington composition typical of a Johnny Hodges small group session. Cullum Band pianist John Sheridan composed “Evening Shadows,” performed here by Brian Ogilvie on alto saxophone, as a tribute to Johnny Hodges.

Lester Young photo courtesy allmusic

Lester Young enjoyed listening to recordings by a group of young white musicians out of Chicago, known informally as Bix Beiderbecke and his gang. Frank Trumbauer played the now-extinct C-Melody saxophone, and was Young’s particular favorite. Lester Young confessed that Trumbauer’s inspiration was key in the development of his own personal style. Out of the Beiderbacke-Trumbauer legacy, emerged a group of teenagers called the Austin High Gang.

Tenor saxophonist Bud Freeman was part of this gang, and developed his own jazz saxophone style influenced by the musical genius of both Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke. Freeman had a long and brilliant career from the 1920s on up to his death in 1991. In 1933 Bud Freeman wrote his most famous tune, a complicated number titled, “The Eel.” Here, Ken Peplowski tackles it. “The Eel” was originally recorded on an Eddie Condon-led date with Pee Wee Russell on clarinet. Also on this broadcast are staples of the Condon mob, like “That Da Da Strain.”

Photo credit for Home Page: Ken Peplowski courtesy of the artist.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1994