There was a time when the trombone was a centerpiece of America’s popular music—a popular instrument with mainstream celebrity players. Today, the trombone is rarely heard except in brass marching bands, symphonic performances or traditional jazz bands. In spite of efforts by a handful of artists, including Troy Andrews (aka ‘Trombone Shorty’) and the Lincoln Center Orchestra’s Wycliffe Gordon, the trombone is seldom a featured solo instrument in jazz. Like the clarinet, the trombone sometimes seems to be facing extinction in the jazz world. But that wasn’t always the case.

Across America in the 1890s summertime meant parasols and picnics in the park, and often a municipal concert wind band (sometimes called a “brass” band) playing polkas and marches, or the folk songs of Stephen Foster. The John Phillip Sousa Band was the pride of the nation, and every town had its own concert band to play for parades, political rallies, Sunday concerts, and to welcome visiting dignitaries as they rolled into town on the train.

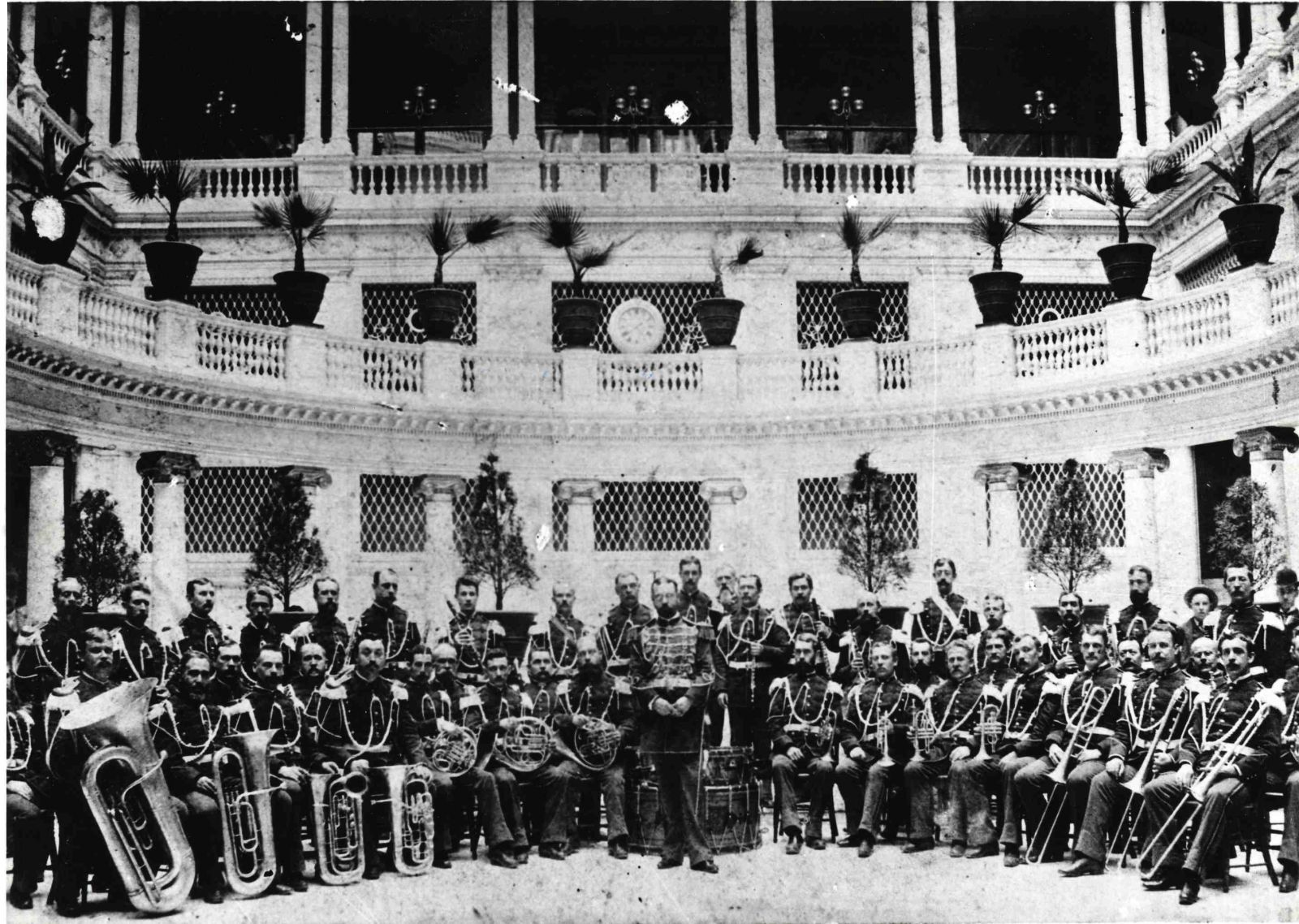

John Philip Sousa and the Marine Band in April 1892 at the Palace Hotel, San Francisco, Calif. Public domain

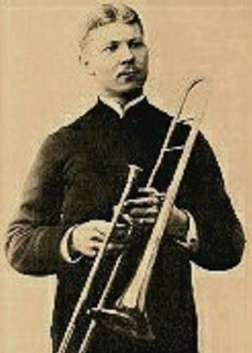

Virtuoso trombonist Arthur Pryor, a star of John Phillip Sousa’s band, was often billed as the “boy wonder from Missouri.” The son of a bandmaster, he was born in St. Joseph Missouri in 1870. His father schooled him in the violin and cornet, but when Arthur became fascinated with a beat-up trombone, his father sent him out to the barn to learn how to play it on his own. Pryor was 21 when he joined the Sousa Band in New York in 1892. Audiences and musicians alike were dazzled with his brilliant and incredibly fast playing. While on tour in Europe, German Army Band trombonists were so amazed at his playing they insisted on taking his trombone apart, refusing to believe it was his talent and not some gimmick in his horn responsible for his spectacular playing.

Arthur Pryor. Photo courrtesy last.fm

Arthur Pryor’s celebrity meant the trombone became an increasingly popular instrument across America. And as jazz emerged around the turn of the 20th century in the Crescent City, the trombone already had a place in the city’s ubiquitous brass marching bands and soon migrated to the front line of New Orleans-style jazz bands.

On this edition of Riverwalk Jazz we celebrate the trombone in jazz and sample the music of Kid Ory, Jack Teagarden, Vic Dickenson, Tommy Dorsey and Abram “Abe” Lincoln. Special guests are trombonist Dan Barrett and vocalist Banu Gibson. By the early 1900s brass bands in New Orleans began to develop a new sound, quite different from their counterparts in the rest of the country—they started to swing. Even before the Great War in 1914, these bands were a breeding ground for a new generation of horn players who would become stars of the jazz world. Kid Ory was among the first to set the standard for the jazz trombone.

Kid Ory. Photo courtesy doctorjazz.co.uk

The unique style that Ory and others developed is often called “tailgate trombone.” In the early days of jazz, bandleaders would commandeer horse-drawn furniture wagons, crowd the players in the back and drive the through the neighborhoods “ballyhooing,” that is, playing to promote that night’s gig. Because trombone players had to deal with the action of the long slides of their horns, they’d sit at the tailgate, which would be let down to give them more room. “Ory's Creole Trombone,” heard here, dates from the era of the “tailgate trombones.”

J.C. Higginbotham was born in Georgia in 1906. By the 1920s he was playing trombone with Louis Armstrong, an association that continued well into the 1960s. Higginbotham was one of the pioneers of the jazz trombone in the Swing Era, playing in dance orchestra led by Fletcher Henderson, Chick Webb and Lionel Hampton. He emerged as one of the great improvisers on the trombone in early jazz. He developed a more sophisticated, melodic approach than the purely rhythmic style of the tailgate trombonists. Stylistically, Higginbotham was a stepping-stone to the great virtuosity of Jack Teagarden. On our show this week, trombone master Dan Barrett pays tribute to both Higginbotham and Teagarden with “I'm Confessin' That I Love You.”

Cozy Cole on Drums –then L to R: JC Higghinbotam, Clyde Newcombe, Rex Stewart, Billie Holiday, Harry Lim, Eddie Condon, Gown Brad, Lipps Page. Courtesy jazzinphoto.com

A leader of the East Coast school of jazz in the 1920s, trombonist Miff Mole was influenced, as many musicians of the time were, by Jazz Age cornet giant Bix Beiderbecke. However Miff Mole developed his own completely recognizable style, distinguished by the remarkable series of intervals he played. Just when you might expect him to reach up the scale for a note, he would reach down instead. From 1925-30 Miff Mole teamed up with cornetist Red Nichols and made a series of jazz recordings under various studio band names, involving New York’s top players. Every time Red and Miff went into the studio, they came up with another wild name for their band. There was Miff and Red’s Stompers, The Red Heads, and Miff Mole and the Molers. In 1926 they recorded Hoagy Carmichael’s “Boneyard Shuffle,” heard here, under the name The Arkansas Travelers.

Tommy Dorsey. Photo courtesy Wikimedia.

In 1927, when cornetist Red Nichols left the Whiteman Orchestra, it was six months before Bix Beiderbecke joined the band and took over cornet duties. In the meantime, rising-star trombonist Tommy Dorsey did double duty, playing lead on both trombone and cornet. Here Dan Barrett pays tribute to Dorsey’s remarkable “doubling” skill on the two brass instruments, duplicating it here on “It Won't Be Long Now.”

Later Dorsey would become the most successful of all the Swing Era trombonists, leading his own enormously popular ensemble. He was ambitious—some would say ruthless—in his pursuit of stardom. Dorsey led his own big band, owned a nightclub in Santa Monica, CA, and was the star of his own long-running national radio broadcast series on NBC. He had a string of hit recordings in the late 1930s through the 1940s, including “Song of India,” “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” and “On the Sunny Side of the Street.” Dorsey’s signature sound can be heard in his flawlessly smooth-sounding trombone playing, which was guaranteed to evoke a romantic mood. To create a showcase for his sound he raided competing bands, luring away the best instrumentalists he could find. His tactic was to write blank checks, and it worked with stars like Yank Lawson, Bud Freeman and Max Kaminsky. On this broadcast, Jim Cullum Jazz Band trombonist Mike Pittsley tackles a tour-de-force piece Dorsey created to show off his great command of the trombone, “Trombonology.”

Young Jack Teagarden. Photo courtesy Red Hot Jazz.

At the peak of the trombone’s popularity in the Swing Era, Jack Teagarden was the brightest star of the instrument. Born in Vernon, Texas, Teagarden got his start at the Horn Palace in San Antonio. He then went to Houston and Galveston to work with pianist Peck Kelley. He was only eighteen years old when he toured the Western states billed as “the South’s greatest sensational trombone wonder.” By the late 1920s Teagarden was a seasoned musician, gaining a solid reputation throughout the jazz world. In 1928 he took New York by storm. Shortly after Teagarden came to town, he was called in as a replacement for Miff Mole on a recording date, and that sealed Teagarden’s triumph on the New York jazz scene. Bandleaders Red Nichols, Glenn Miller and the Dorsey brothers were bowled over by his playing. From then on, Teagarden was in demand for every session. “Diane,” heard here, is one of the titles Teagarden made his own in 1938 on a classic recording with Eddie Condon, Bobby Hackett and Bud Freeman.

Jack Teagarden truly revolutionized jazz trombone playing. Before he came on the scene, the trombone was used to reinforce the rhythm and notes of the bass, but Jack came forward with a new, more melodic approach, playing true counter-melodies to the trumpet. Teagarden was a great improviser and advanced trombone playing to a new level of music. Technically, Jack Teagarden was an innovator as well. He had tremendous control with his lip. As a result of this flexibility he played what are called “false positions” using unorthodox slide positions to achieve his amazing virtuosity. Jim Cullum says, “The net result was a lot of beautiful jazz. And he was a great singer, too, especially on numbers like ‘A Hundred Years from Today,’ which I remember him singing.”

Vic Dickenson. Photo courtesy of last.fm

Born in Ohio in 1906, Vic Dickenson was one of the most versatile trombonists to come out of the Swing Era. Listening to recordings of Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds when he was boy inspired Vic to learn how to play the trombone. In the 1920s Vic barnstormed through the Midwest with a series of regional bands, developing his trombone style on the job. In the 1930s he launched his recording career as a session man in New York, famous for his encyclopedic knowledge of tunes. Dickenson’s big break came in 1940 when he signed up with Count Basie, and began sharing the bandstand with all-time great players in jazz—Lester Young, Sweets Edison and Buck Clayton. Dickenson had a long and distinguished career in jazz, continuing to work well into the 1970s. He played in bands led by Sidney Bechet, Bobby Hackett, Eddie Condon and Benny Carter.

A less famous but highly-rated trombonist of the Swing Era got his start—like Tommy Dorsey—with a 1920s group called the California Ramblers. Abram “Abe” Lincoln worked with Paul Whiteman, Roger Wolfe Kahn and Ozzie Nelson and made a string of high-powered recordings with a group in Los Angeles centered around clarinetist Matty Matlock. Never compelled to seek fame and fortune, Abe Lincoln had a workman-like approach to his music. According to his son, Abe Jr., “he always went to a recording session to win and gave 100%.” Lincoln would step back and leave the music business behind once the session was over.

The Bud Lincoln Orchestra L to R: Drums, Bugs Boganoff; Piano, Frank Whitman; Banjo, John "Fat" Dibert; Trumpet, Bud Lincoln; Sax, Sammy Dibert; Trombone, Abe Lincoln. Photo courtesy Abe Lincoln Jr.

Trombonist Mike Pittsley was inspired by Lincoln’s playing early in his career and befriended the little-known giant of jazz trombone in his later years. Pittsley first heard Lincoln’s fiery approach to hot trombone playing on a 1955 LP, Coast Concert and recalls, “It was the level of energy and excitement Lincoln could project through his playing that blew me away.” Lincoln’s advice to Pittsley: “Remember, save half of what you earn and you’ll be all right.” On this broadcast Mike Pittsley teams up with guest trombonist Dan Barrett for a tribute to Abe Lincoln, “I Ain't Gonna Give Nobody None of My Jelly Roll.”

Photo credit for Home Page: Dan Barrett photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1995